Table of Contents

Contact Hypothesis

About 'The Nature of Prejudice'

Some inconsistencies in the book: Is prejudice a normal cognitive process or an irrational ego-defensive maneuver? Can be both.

Are stereotypes the cause or the consequence of prejudice? Once again can be both, Stereotypes rationalize the emotional dispositions

Allport’s Intergroup Contact Hypothesis: Its History and Influence

“The Social Science Research Council then asked the Cornell University sociologist, Robin Williams Jr., to review the research on intergroup relations. Williams’s (1947) monograph, The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions, offers 102 testable “propositions” on intergroup relations that included the initial formulation of intergroup contact theory. Based on the scant research available, Williams (1947) stressed that intergroup contact would maximally. reduce prejudice when: (a) the two groups share similar status, interests, and tasks; (b) the situation fosters personal, intimate intergroup contact; © the participants do not fit the stereotyped conceptions of their groups; and (d) the activities cut across group lines. These general principles will be familiar to anyone versed in Gordon Allport’s framework.”

“From the student papers especially, Allport noted the contrasting effects of intergroup contact – often reducing but sometimes exacerbating prejudice. To account for these inconsistencies, Allport adopted a “positive factors” approach. Reduced prejudice will result, he held, when four positive features of the contact situation are present: (a) equal status between the groups, (b) common goals, © intergroup cooperation, and (d) the support of authorities, law, or custom.”

Equal group status in the situation

“What is critical is that both groups perceive equal status in the situation (Cohen, 1982; Riordan & Ruggiero, 1980;Allport’s Intergroup Contact Hypothesis 265 Robinson & Preston, 1976).”

In a robotic telepresence scenario this implies that both sides need to be hidden behind a robot. But what about the asymmetry in the starting conditions?

“research demonstrates that equal status in the situation is effective in promoting positive intergroup attitudes even when the groups initially differ in status (Patchen, 1982; Schofield & Eurich-Fulcer, 2001).”

Common goals

“Effective contact usually involves an active effort toward a goal the groups share” (Military, athletics, work tasks etc).

In robotic telepresence that does mean a common game or task?

Intergroup cooperation

“Attainment of common goals should be an interdependent effort based on cooperation rather than competition.”

Does this take into account context, mediated goals, different value sets?

Support of authorities, law, or custom

“Intergroup contact will also have more positive effects when it is backed by explicit support from authorities and social institutions.”

civil-rights legislation

Can it be that does conditions are in fact limiting and circumscribing intergroup contact? What happens when the contact is forced to take place within structures that are part of the cause of the conflict? Is this forced normalization?

Analysis

“Allport held that his four conditions should be integrated and implemented together, rather than listing them as variables to be considered individually” So they considered only two: Intergroup friendship (equality and cooperation) and Structured programs for optimal contact (an organized intention to meet Allport's condition).

Have these studies considered long-term effects for thees contacts? Do we have an improvement or worsening of prejudice on a global level?

Future Directions in Intergroup Contact Theory

“with an ever-expanding list of necessary conditions, it becomes increasingly unlikely that any contact situations could meet these highly restrictive conditions (Pettigrew, 1986, 1998; Stephan, 1987)”

“intergroup contact typically leads to positive outcomes even when no intergroup friendships were reported and in the absence of Allport’s proposed conditions. Indeed, 95 percent of the 714 samples included in our meta-analysis reported that greater intergroup contact corresponds with lower intergroup prejudice; but only 10 percent of the contact measures involved intergroup friendship and only 19 per- cent of the samples reported contact under Allport’s conditions. In hisformulation, Allport held his optimal factors to be essential conditions for intergroup contact to diminish prejudice. But our results indicate that, while these factors are important, they are not necessary for achieving positive effects from intergroup contact. Instead, Allport’s conditions are better thought of as facilitating, rather than essential, conditions for positive contact outcomes to occur”

So it is known that these conditions aid in increasing prejudice, but they are not necessary. On the contrary it is not really known what are the negative factors that could even cause an increase in prejudice.

“In many ways, this stance reverses Allport’s approach. It starts with the prediction that intergroup contact will generally diminish prejudice, but the magnitude of this effect will depend on the presence or absence of a large array of facilitating factors – not just the four emphasized by Allport. In particular, this approach focuses special attention on those negative factors that can subvert contact’s typical reduction of prejudice”

- “participants who do not think intergroup contact is important show far less prejudice reduction than those who regard it as important” (Van Dick et al., 2004).

- “Emotions such as anxiety and threat are especially important negative factors in the link between contact and prejudice” (Blair, Park, & Bachelor, 2003; Stephan et al., 2002; Stephan & Stephan, 1992; Voci & Hewstone,2003; see also Stephan & Stephan’s ch. 26 in this volume)

- The type of intergroup matters too (difference race, sexual orientation, political opinion etc)

How about the uncanny valley of mediation?

Intergroup Contact: When Does it Work, and Why?

“Allport warned that superficial contact between members of dif- ferent groups would, in fact, reinforce stereotypes, by failing to provide new information about each group,” Thus he wrote, “the casual contact has left matters worse than before” (Allport, 1954/1979, p. 264).

Allport warned: “whether or not the law of peaceful progression will hold seems to depend on the nature of the contact” (p. 262).

“ The decategorization model (Brewer & Miller, 1984) proposed minimizing the use of category labels altogether, and instead interacting on an individual basis. The recategorization model (e.g., Gaertner, Mann, Murrell, & Dovidio, 1989) suggested that intergroup contact could be maximally effective if perceivers rejected the use of “us” and “them” in favor of a more inclusive, superordinate “we” category. These two models can be seen as extensions to Allport’s notions of perceived similarity between groups and, to a lesser degree, equality of status. Another model (Hewstone & Brown, 1986), called categorization (or sometimes mutual intergroup differentiation) pointed out practical problems with personalized, as opposed to group-based, interactions, and instead promoted keeping group boundaries intact and salient during intergroup encounters. Nevertheless, despite their conceptual differences, all of the various models that followed Allport paid a tribute to his ideas in some fundamental way.”

Developments Since Allport

Allport believed “contact must reach below the surface in order to be effective in altering prejudice” (p. 276). Incarnation/Physicality?

- Individual connection vs 'remembering' the group affiliation.

“Hewstone and Brown (1986) argued that, under decategorized contact, attitudes towards the outgroup as a whole would remain unchanged”

This brings a point about telepresence and avatars in general. How much should the group affiliation be kept and mentioned?

In a personal approach “they are likely to be subtyped, or cognitively processed as separate from the group as a whole, or treated as an individual with no connection to the overall group….Nevertheless, practically, for categories that are visually salient (e.g., race, gender), complete decategorization is unlikely to occur, thus providing some basis for the benefits of positive personalized interaction to generalize to attitudes to the group as a whole (Miller, 2002).”

“Although it is not necessary that categorysalience be maintained at all times (see van Oudenhoven, Grounewoud, & Hewstone, 1996), ideally it should occur before the outgroup individual is perceived as atypical of their group.” How would the robot show its group affiliation right away?

“Emphasizing categorization during contact, however, is not without its own dangers. Making categories salient risks exacerbating and reinforcing perceptions of group differences, which may result in anxiety, discomfort, and fear (Hewstone & Brown, 1986)”

A robot however is much less threatening, supposedly. Need to be careful of the uncanny affect causing anxiety

“A theoretical paradox had thus arisen: whereas interpersonal encounters were likely to be pleasant, they might fail to generalize without some salience of group membership; conversely, salient intergroup encounters could generalize to the whole outgroup, but might be undermined by the concomitant generation of intergroup anxiety (viz., “anxiety stemming from contact with outgroup members”; see Stephan & Stephan, 1985, p. 158; see also Smith & Mackie, ch. 22 this volume).

- cognitive subtyping - regarding an outgroup individual as 'exceptional'.

- Eliminating categories / prejudice - assimilation (my incarnation).

“The combined perceptions of disclosure (interpersonal) and typicality (intergroup) reduced subsequent bias toward new outgroup members, who themselves had no connection to the confederate other than shared group membership (Ensari and Miller)..Recent research shows cross-group friendship (i.e., intimate contact with a member of the outgroup) to be a particularly effective form of intergroup contact (Pettigrew, 1997). Moreover, even indirect contact (i.e., the mere knowledge that other ingroup members have friends in the outgroup; Wright, Aron, McLaughlin-Volpe, & Ropp, 1997), can lead to more positive intergroup attitudes. These findings indicate the importance of the intimacy of contact and its potential to personalize the outgroup member, but they also suggest that despite the importance of a personalized interaction, some level of category salience must also be maintained if positive attitudes are to generalize to other members of the outgroup category.”

In short, the interlocutor has to keep in mind they are conversing with an outgroup member, but they need to be able to develop a personal relationship. The robot has to be designed with some features that associate it with the group

A New Framework: How Does Intergroup Contact Work?

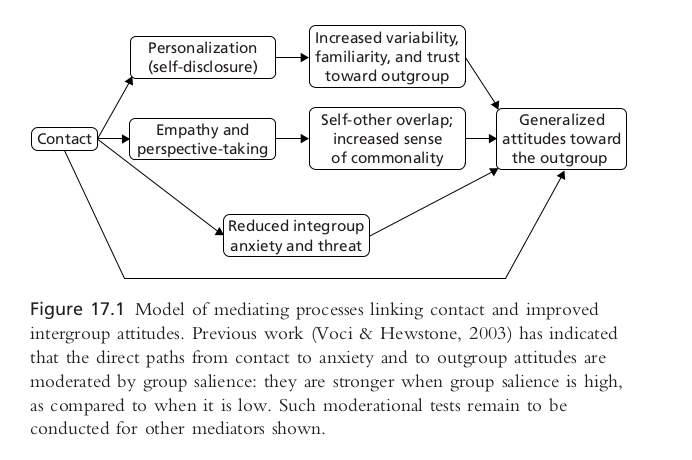

“contact per se typically has a reliable and independent effect (e.g., bottom path of figure 17.1) on the reduction of prejudice.”

- Two perspectives: moderation (What happens when the contact works) and mediation (How it happens).

“Although affective factors are now considered to be particularly important (see Pettigrew, 1998), individuation and self-disclosure – factors that have both cognitive and affective elements have also been found to mediate the relationship between intergroup contact and improved outgroup attitudes (e.g., Turner, Hewstone, & Voci,2005).”

Optimal contact process: Three stages:

- Decategorization / individuation: The contacted individual is separated from the group to which there are prejudice.

- Categorization: After growing sympathy to the individual, its relation to the group is re-thought and creates a more positive outlook on the entire group.

- Recatogrization: The outgroup is no longer considered 'out', but we are all seen in one common group.

“Pettigrew’s model suggests that mediators and moderators might work together to produce the optimal contact situation (see Brown & Hewstone, in press).

In a robot situation the mediating and moderating elements are the robot itself, its interface and nature of interaction - this also bears the question of what is the level autonomy of the robot? Can it act as a mediator? This would reduce the authenticity of the avatar.

Dovidio, Gaertner, and Kawakami (2003) name cognitive factors and affective factors that mediate the contact.

Cognitive Factors

Learning general information about the outgroup does not necessarily help reduce prejudice, but learning specific information about the individual that separates them from the outgroup stereotypes helps.

Self-disclosure from the individual helps because it amplifies the individual complexity of every individual that is independent of the group stereotypes. Self-disclosure also has an affective value because it generates intimacy and trust.

Affective Factors

”affective factors appeared to be much more influential. Specifically, Pettigrew and Tropp (2000) concluded that anxiety appears to be a more important link between contact and reduced prejudice than is increased knowledge of the outgroup..Intergroup anxiety is thought to stem from the anticipation of negative consequences during contact, such as embarrassment, rejection, discrimination, or misunderstanding, and may therefore be exacerbated by minimal prior contact with the outgroup and large status or numerical differences between the ingroup and the outgroup (Stephan & Stephan, 1985). Anxiety may also result from intergroup threat, either symbolic or realistic, adistinction that is prominent in Stephan and Stephan’s (2000) Integrated Threat Model. Symbolic threat is conceptualized as a threat to the value system, belief system, or worldview of the ingroup, whereas realistic threat is a threat to the political and economic power, or physical well-being, ofthe ingroup”

This relates to stranger fetishism and deep political emotions.

Of course cognitive and affective processes are linked.

“argument put forward by Wright et al. (1997), namely, that when one observes a fellow ingroup member interacting with an outgroup member, not only is there less immediate anxiety because the observer is not directly involved in the contact situation, but anxiety about future possible intergroup interactions will also be lessened by reducing the fear (affect) and negative expectations (cognition) that tend to cause anxiety prior to actual contact.”Or

Good justification for public space and joint conversations. And also robots that don't make you anxious.

Perspective taking of course leads to empathy, but how does one do that in a robot encounter? Has to be mediated/moderated some way? Or by showing first person data by the controller?

“a combination of positive contact and group salience during that contact resulted in the most positive evaluations of the outgroup. This methodological innovation can make a unique contribution to the future understanding of the contact hypothesis.”

The Contact Hypothesis Reconsidered: Interacting via the Internet

Defines significant barriers to initiating contact:

- Practicality: meetings are complicated to arrange, language barriers, status difference, physical barriers/distance.

- Anxiety: anticipation of negative reactions leads to increased usage of stereotyping. During state of anxiety positive 'subtyping' is ignored.

- Generalization (categorization): Tricky to achieve. It is still unclear how much group saliency is needed, and how to measure this. Group saliency levels can be explicitly determined in a robot telepresence scenario, using the design of the robot and of the deployment site .

The Net Advantage

Equal status

Equal status can be divided to: external equal status (in real life) and internal equal status (within the contact).

”As Hogg (1993) has shown, within group interactions people tend to be highly sensitive in discerning subtle cues that may be indicative of status. Online interactions have the advantage here because many, although not all, of the cues individuals typically rely on to gauge the internal and external status of others are not typically in evidence..such is not the case in electronic interactions. One aspect of electronic communications that has long been decried (e.g., Sproull & Kiesler, 1991) is the tendency,within organizational settings, for there to be a reduction in the usual inhibitions that typically operate when interacting with one’s superiors. In other words, existing internal status does not carry as much weight and does not affect the behavior of the group members to such an extent. Underlings are more likely to speak up, to speak ‘‘out of turn,’’ and to speak their mind. Thus electronic interaction makes power less of an issue during discussion which leads group members, regardless of status, to contribute more to the discussion (Spears, Postmes, Lea, & Wolbert, 2002). While this can prove to be problematic within a corporate setting, it is advantageous in the present context, as the medium serves to reduce the constraining effects of status both within and between the two groups..“

However this could also lead to lack of empathy and agency and some negativity in conversation. In robotic telepresence the experience is different because you are still embodied and communicating physically, but it depends on elements such as feedback and reciprocity. For the robot controller they are able to assume another body which affects the perception of their status.

Connecting from Afar and with the Comforts of Home

“having participants engage in the contact from the privacy of their respective homes has distinct advantages. Participants are likely to feel more com fortable and less anxious in their familiar surroundings. Further, research has shown that public, as opposed to private, settings can exacerbate the activation and use of stereotypes, especially when it comes to those tied to racial prejudice (e.g., Lambert, Payne, et al., 2003). As Zajonc (1965) has shown, an individual’s habitual or dominant response is more likely to emerge in public settings, whereas the individual is likely to be more open and receptive to altering the habitual response when in a private sphere. Even when participants interact in quite ‘‘public’’ electronic venues but do so from the privacy of their homes, they tend to feel that it is a private affair (e.g., McKenna & Bargh, 2000; McKenna, Green, & Gleason, 2002). Thus, interacting electronically from home should serve to inhibit the activation of stereotypes as compared to a more public and face-to-face setting in a new environment.”

But this might also reduce generalization? Also when placing a robot in the public space you are able ot reach an audience that still wouldn't take the initiative to join an organized encounter

Cooperation Toward Superordinate Goals

“the benefits of including virtual teams have become more evident (Cascio, 2000). For instance, employers find that telecommuting increases worker productivity and improves attendance (Abreu,2000)…Galegher and Kraut (1994) also found that for virtual work groups the final product was similar in overall quality to that produced by face-to-face group members.”

There are a lot disadvantages with lack of body language and synchrony in without face-to-face contact. Also gathering virtual teams to work on a task is very difficult in situations of conflict and barriers

Institutional Support and Willingness to Participate

“If the organization has compelled its members to take part in the meeting, they are unlikely to change their stereotypes as a negative reaction to the feelings of loss of control over their freedom of association (Stephan & Stephan,1996). Participating in an Internet contact may be seen as taking on less of a risk than a face-to-face contact (Bargh & McKenna, 2004; McKenna & Bargh, 1998) and this may make it easier for group members to volunteer to participate and for leaders to support such a meeting.”

This might also mean that the participants are more alienated and less liable to assimilate new meanings

Bridging the Language Barrier

This is now of course possible, but the danger and embarrassment enclosed in misunderstandings is also disruptive

Ameliorating Anxiety Through Online Interaction

”many of the situational factors that can foster feelings of anxiety in social situations (e.g., having to respond on the spot, feeling under visual scrutiny) are absent in online interactions. Because participants have more control over how they present themselves and their views online (e.g., being able to edit one’s comments before presenting them), they should tend to feel more comfortable and in control of the situation. They should be better able to and to more often express themselves, to be liked more by their online interactions partners than if they inter- acted in person, and to develop closer, more intimate relationships through online interaction“

“Those experiencing anxiety in social situations have also been found to take more active leadership roles in online groups than in their face-to-face counterparts. In a study by McKenna, Seidman, Buffardi, and Green (2005)”

Supersize It: Generalizing from the Contact to the Group

”One of the advantages of online communication is that one can quite easily manipulate the degree of individual versus group saliency in a given contact situation in order to achieve a desired outcome. Spears et al. (2002) have argued that anonymous communication within groups leads to a sense of depersonalization by the group members. That is, members feel an absence of personal accountability and personal identity and thus the group-level identity becomes more important. When the group-level identity is thus heightened, Spears et al. (2002) have shown that group norms can have an even stronger effect than occurs in face-to-face interactions. The degree to which the group identity is salient, however, plays an important role in determining what the effects of anonymity will be on the development of group norms.“

”One of the most interesting sets of studies examining the interaction between anonymity and identity-salience tested the effects of primed behavior in electronic groups. Postmes, Spears, Sakhel, and De Groot (2001) primed participants with either task-oriented or socioemotional behavior and then had them interact in electronic groups under either anonymous or identifying conditions. Members in the anonymous groups displayed behavior consistent with the respective prime they received considerably more so than did their counterparts who interacted under identifiable conditions within their groups.“

Some 'priming' perhaps could be achieved by co-designing the robot with certain features

“one can provide all members with anonymous screen names that are evocative of the group they are representing (e.g., Pakistan 1, India 1, Pakistan 2) or, following Leah Thompson’s procedure (see Thompson & Nadler, 2002) one can have each member briefly introduce him- or herself at the beginning of the interaction and ask each to include a statement stressing his or her typicality as a member, and so forth. As the inter- action in the online environment progresses, group norms will begin to quicklyemerge (Spears et al., 2002). These norms will be distinct from those that operate when members of group A are alone together and distinct from those unique to group B. Rather, these norms will emerge from the combined membership of groups A and B in the online setting, leading to heightened feelings of attachment and camaraderie among the participants. Thus, one can effectively invoke the necessary balance of a sense of both ‘‘us and them’’ among the participants that will allow for acceptance and generalization.”

Getting More than just Skin Deep

“One of the major advantages of Internet interactions over face-to-face interactions is the general tendency for individuals to engage in greater self-disclosure and more intimate exchanges there. Interactions online tend to become ‘‘more than skin deep’’ and to do so quite quickly (e.g., McKenna et al., 2002; Walther, 1996). Spears and Lea (1994) suggest that it is the protection of anonymity often provided by the Internet that helps people openly to express the way they really thinkand feel. In line with this, McKenna and Bargh (1998, 1999) suggest that this sense of anonymity allows people to take risks in making disclosures to their Internet friends that would be unthinkable to them in a face-to-face interaction…even without the cloak of anonymity, people more readily make intimate disclosures through their Internet interactions than through their face-to-face interactions, even when it comes to their nearest and dearest.”

Intimacy facilitators:

- a greater sense of anonymity or non-identifiability that leads to a reduced feeling of vulnerability and risk.

- the absence of traditional gating features to the establishment of any close relationship—that is,easily discernable features such as physical appearance (beauty is in the eye of thebeholder), mannerisms, apparent social stigmas such as stuttering, or visible shyness or anxiety;\

- a greater ease of finding others who share our specialized interests and values—and particularly so when there are a lack of ‘‘real world’’ counterparts (e.g.,because of the marginalized or highly specialized nature of the interest, such similarothers may not be present in one’s physical community or, if they are, they are not readily identifiable)

- more control over one’s side of the interaction and how one presents oneself.

Beyond the Cookie-Cutter Contact: Tailoring the Net Contact to fit Specific Needs

“The anonymity and identifiability of participants can be manipulated depending on the particular needs of the situation and can be altered over time. The salience of the originating group and that of the ‘‘new group’’ can be heightened or lowered as needed”

In a robot interface as well controllers can choose for example to record their own voice, or in cases where there is a display, show their face or other details. Also when designing the robot they can choose the level of salience

An integrative theory of intergroup contact

Four major components to intergroup contact:

Dimensions of Contact

Measurement of contact

- Quantity and quality of contact.

- Cross group friendships are a good measurement.

- Extended contact should be assessed.

- Examine social networks and not just dyadic contact.

Moderating variable - group contact

We have subsequently proposed, simply, that group membership must be suffciently salient to ensure generalization but not so salient that it leads to intergroup anxiety or otherwise exacerbates tensions (Hewstone, 1996, p. 333). As our moderated mediation approach emphasizes, participants who are relatively more aware of group memberships. during contact are, in fact, those most likely to benefit from the cumulative, anxiety-reducing eVect of repeated exposure to the out-group (e.g.,Harwood et al., in press, Study 2; Voci & Hewstone, 2003b, Study 1). Intuitively, our sense is that the optimal measure of moderation refers to awareness of group aYliations or perceived typicality of out-group partner(s). Where tensions are high, however, an item such as ‘during contact we discuss intergroup differences’ may trigger negative intergroup differentiation.We note three future priorities for research on moderation. First, we need systematic studies of which measures of salience are best moderators of contact effects and which, if any, actually have negative effects…Second, when should salience be introduced into the contact setting? Third, there is a need for further research on generalization.

Mediating variables

In its first version, our model emphasized various cognitive processes that we believed would lead to positive (or negative) outcomes of contact (social categorization, stereotyping, expectancies, and attribution processes). This led to our work on the cognitive processes implicated in stereotype changereviewed in Section IV. However, the subsequent decade (prom*pted by Pettigrew, 1986) saw a gradual shift in emphasis to more affective mediators, starting with intergroup anxiety, which has proved to be a potent variable in several contexts.

five possible mediators: intergroup anxiety, perspective-taking (empathy?), individuation, self-disclosure, and accommodation.

Outcome measures

We have found that measures of intergroup affect (liking), trust, and forgiveness are all predicted by various kinds of contact, either directly or indirectly.

Why Can't We Live Together? - Miles Hewstone

? Quantity of contact: frequency of the meetings. Quality of contact : The nature of the contact, how positive/negative,

Indirect contact (“I have a friend who knows..”) lowers anxiety toward the outgroup.

In a school study, even though the attitude toward miniority and the norms were generally positive, at lunch time cafeteria the students still choose to sit in homogenous groups, when they are given the choice. Should we use 'social engineering' to create contact? Should the robot 'pop-up' to force contact?

From the original 'nature of prejudice'

In studies regarding the employment of African-Americans and “FEPC” (p.274), two conclusions seem to emerge:

- It helps if the new employees are incorporated in different levels of proficiency, not just the bottom of the scale.

- It is best to not raise the topic to discussion, because then it will spur much resistance. It is best to just force it and let the small flurry of resistance quiet down. The impending contact elicits more protest than the actual contact. Does this give advantage to a 'pop-up' robot/unstructured encounter rather than an organized session?*

“People may come to take for granted the particular situation in which contact occurs, but fail to completley generalize their experience. They may, for example, encounter Negro sales personnel in a store, deal with them as equals, and yet still harbor their over-all anti-Negro prejudice. In short, equal-status contact may lead to dissacoiated, or highly specific, attitude, and may not affect the individual's customary perception and habits. The nub of the matter seems to be that contact must reach below the surface in order to be effective in altering prejudice. Only the type of contact that leads people to _do_ things together is likely to result in changed attitudes. The principle is cleraly illustrated in the multi-ethnic athletic team.”

Hypothesis - not just a common goal but also learning by doing, adding a physical dimension to the interaction